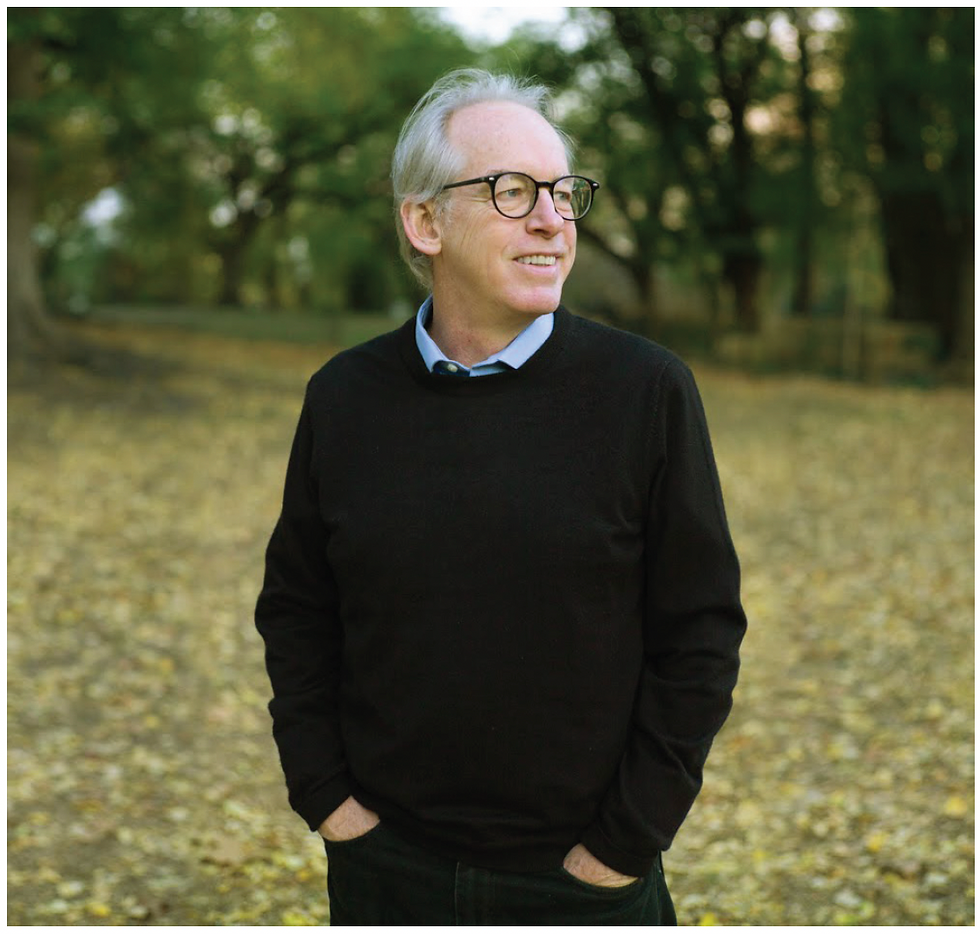

An Hour with Michael Cunningham

- Anastasia Stanmeyer

- Sep 1, 2023

- 10 min read

Updated: Sep 8, 2025

THE PULITZER PRIZE-WINNING AUTHOR HAS TIME TO TALK ABOUT HIS WRITING

Fall 2023

By Anastasia Stanmeyer

MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM SITS IN HIS STUDIO in the West Village. Behind him and in front of him, his books and papers are impressively well-organized. Beyond the camera’s lens, the room isn’t so orderly, he says jokingly at the start of the Zoom interview. Similarly, he’s got a lot swirling around him. He was supposed to be writing the pilot of a TV show for a cable network, but they’re on strike. His eagerly anticipated novel, Day, is set to be released November 14, but he can’t talk details. (Published by Penguin Random House, Day is a family saga set in New York City before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.) Cunningham resumes teaching at Yale University for the fall semester, which begins on August 30. The Hours opera, adapted from his novel of the same name, will return to The Met after a sold-out world premiere last season. And, in the Berkshires, Cunningham will be in conversation on September 23 with Roxana Robinson at the WIT Festival, on the topic of “Mrs. Dalloway at 98.” Cunningham received the PEN/Faulkner Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1999. Currently professor in the practice of creative writing at Yale, he also has taught at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown and at Brooklyn College. He has a gap of time to catch up on things and to reflect. We begin our talk.

Have you ever been to the Berkshires? My best friend from college went to medical school, specialized in psychiatry, and did her residency at Austen Riggs in Stockbridge. She finished her internship and her residency and got a job in California. I not only miss her and her husband and their two sons, I miss the Berkshires. I think this happens to a lot of us: You have a friend in a place, the friend leaves the place, and that kind of takes the place away with them.

What do you think about when you think about the Berkshires? We had such great times up there. I certainly romanticized it. We would go for swims in a lake near where they lived, we’d go for hikes, and they were renting this fantastic house with a front porch and a fireplace. We just had nothing but great times.

Let’s talk about someone you know very well—Virginia Woolf. What first drew you to Mrs. Dalloway? I grew up in Los Angeles and was a not very rigorous student at a not very rigorous public school. I had a crush on a girl who was just so beautiful and smart and terrifying to almost everybody. I was talking to her, tentatively, in terror, and she mentioned the fact that she was not only doing the required reading at our school, but also reading outside the curriculum, and she was especially crazy about Virginia Woolf. I thought if I could talk to her about Virginia Woolf, maybe she would fall in love with me or at least stop ignoring me. So, I went to the library—that double-wide on cinder blocks where they kept the books at the school— and Mrs. Dalloway was the only thing by Woolf they had. Let’s say I tried to read it. To my under-read, 15-year-old brain, it was incomprehensible.

Did you get through it? I got through it, but I didn’t get it as a story. What I did get was the language. Those sentences, those big, beautiful, graceful sentences with semicolons and parentheticals. I had never seen prose like that. At our school, they gave us perfectly good books made up of simple declarative sentences in the hopes that we would not be entirely scared off from literature. Sentence by sentence in Mrs. Dalloway, even though I wasn’t always sure what the sentences meant, really knocked me out. I’m afraid I may have said something to this girl, like, “Wow, the language in Mrs. Dalloway is kind of like a guitar riff by Jimi Hendrix, don’t you think?” Which I still stand by, but it didn’t work for her. But that’s what actually, by slow degrees, turned me into a reader. I’m sure I would have figured it out eventually by other means, but I suddenly realized what you could do with language. I started reading more serious books, and I was gone. I never really went back to my skateboarding, rock-and-roll self.

How many times have you read Mrs. Dalloway? Oh, I’ve lost count. It was, of course, many years later when I began trying to write The Hours. I had reread Mrs. Dalloway several times by then. Before I started writing the book, I read it one more time and then put it away and didn’t let myself look at it. I wanted to write that book under the influence of Virginia Woolf without trying to replicate her voice. I put myself on a strict Virginia Woolf diet so I wouldn’t fall into the trap of trying to imitate her.

Is Mrs. Dalloway your favorite Woolf book? I think her next novel, To the Lighthouse, might be her greatest book, with Mrs. Dalloway adjacent. Mrs. Dalloway was her fourth novel and her first really revolutionary one. Jacob’s Room is kind of transitional. One of the things I love about Mrs. Dalloway is you can almost see Woolf teach herself how to write a great novel by writing one. It has a raffish quality and some loose ends. And then she goes on to write To the Lighthouse. I don’t think you can use the word “perfect” to describe a novel, there’s no such thing. But, thanks in part to Mrs. Dalloway, she is now in full possession of her powers. She went from sort of inspired noodling in Mrs. Dalloway to full command in To the Lighthouse. I wouldn’t have done a book like The Hours using To the Lighthouse. If Mrs. Dalloway was a bit of a riff, and you could riff on that. To the Lighthouse has no toeholds or handholds or anything. You just had to leave that one alone.

Depending on the age that you read Mrs. Dalloway, it probably took on different meanings. Oh, absolutely. We who are serious about books are not going to have time to read all the significant books even once. In theory, I think we should read the ones that are most moving to us about once every 10 years. That’s an arbitrary number, but you know what I mean. It’s the same book, but you’re a different person, and you’re going to read it differently.

I read The Hours shortly after it came out, and I’ve seen the movie. I wanted a refresher before our talk, but I didn’t have time to read it again. So I listened to the audiobook. You’re reading it. What was that like? It was a little bit painful. I think a lot of writers feel that way. If you aren’t reasonably happy with a book that you finish, you shouldn’t publish it. At the same time, not long after you’ve turned the final copy in, you start thinking of things you could have done differently: a paragraph here, a line there. Little things and, sometimes, big things, like why didn’t I make them all talking chihuahuas?

Yes, why didn’t you? When I have something published, sometimes it takes me a while to read back on it. I don’t know if it’s because I’m just sick of it at that point, or I’m afraid I’m going to find something that I should have changed, or I’m not sure what it is. Oh yeah, right! For me, it’s some combination of, “Oh, that one could have been better!” And there’s this slightly crazier thing, where I have been walking around for a long time with this impossible idea for a novel floating over my head, impossible in that it would include emotions for which there is no language. It would play music. So I also have to get over the discrepancy between the book itself and this magical book that employs language and also transcends language that no one can write. As I learned, reading for an audiobook is painstaking. It takes a few days. You can’t stumble over any word; you do it over and over and over again. When I say painful, it was the most intimate possible reacquaintance with the things I might have done differently. I don’t want to overemphasize that, though. I’m also happy with the book and pleased and astonished that it has meant so much to so many people.

What is it about the book that you think touched so many? Honestly, I don’t know. I think you never know. I certainly wasn’t writing it thinking, well, this will be any kind of a big deal. After it won the Pulitzer, I remember I was having lunch with my agent and said, “Well, this great. But at least we know no one’s gonna want to make a movie out of it.”

Hah! And it sounds like you’re pretty happy with the movie. I was maybe the only living writer who was happy with a movie made of their novel.

And then there’s the opera. That was yet another surprise.

Were you involved in its making? Not at all. It was agreed that the composer and lyricist should feel full ownership and that it would be better if the novelist was just sort of out of the room, which is fine with me. That was mostly the case with David Hare, who did the adaptation of the movie. If somebody wants to take a story you’ve written and transpose it into another medium, I don’t really want to face all the adaptation. I’d love to see what gifted people will do with it on their own. I went to opening night for the opera along with everybody else.

With The Hours, it was different. You were in the movie. Just for a second. I had two lines, but they were cut.

What did you think when you saw the opera? It was slightly surreal. I loved it. I thought they did a fantastic job. Surreal in that I wrote the novel 25 years ago, and Greg Pierce, the lyricist, didn’t use a lot of my own dialogue. He wrote a lot of it himself, although he did use some of mine. I would hear a line suddenly and remember not only writing it 25 years ago, but thinking, oh, this is the best I can do for now. I’ll go back and rewrite it later. And didn’t. And then, whoosh, Renee Fleming is singing it on the stage at The Met!

Do you think you’re a better writer now than you were ten years ago? How have you evolved as a writer? That’s a really good question. You hope you get at least a little better with each book. That’s obviously not always the case. I don’t need to name names, but we can name a lot of writers whose best books were written relatively early on. I feel like you spend your whole writing life learning how to write fiction, and I’m still trying to learn how to write it. Monet did those insanely beautiful giant waterlily paintings at the end of his career. He wasn’t quite satisfied because he didn’t feel like he was getting the movement of reeds underwater exactly right. At 80-something, he died trying to get those goddamn reeds right. I love the idea of doing a lifetime’s work that never feels finished, that you never feel you have gained real mastery.

What do you still need to work on? I need to invent a new voice for every book, different rhythms, different vocabulary, different whatever, that feels most suitable to that book. My students worry about being overly influenced by the writers they love, and I always tell them don’t worry about that. The worst that’ll happen is that you’ll spend a little time writing fake Alice Munro, or fake Karen Russell. And, believe me, you’re not going to turn into Alice Munro or Karen Russell, but you will have little chips—an Alice Munro chip, a Karen Russell chip—that will affect the way you write. So, go ahead and let yourself be influenced. Let’s just say I have a lot of chips of great writers buried in my brain by now.

You’ve gotten a lot of mileage out of The Hours. Does it ever get old to talk about it? No. There are moments when I think, I wrote other books, too. But then I smack myself and remind myself that it’s amazing that people still want to talk about a book 25 years after I wrote it. Shut the hell up and stop complaining.

Going back to The Hours movie, you said that you wanted them to interpret it the way that they wanted to, and you were quite impressed by the results. What is it about the movie that you thought was great? One thing is you can’t get around the performances of Nicole Kidman, Meryl Streep, and Julianne Moore. Seeing it, one of the things I was really aware of is that there are things you can do in a movie that you can’t really do in prose. There is a moment when Meryl Streep is in the kitchen getting ready for the party, and they’re talking about Richard, and she kind of loses her balance for a second. Which, if you try to write, would seem too obvious. Towards the end, there’s Julianne Moore just losing it in the bathroom and saying to her husband in the bedroom, “I’m fine, everything’s fine,” in a perfectly normal voice. So there was this sense that they had really used what movies can do. The music was fantastic, and just the sort of swirl of it. There is this opening montage of three women all waking up. It felt compact in a way that I really loved.

Let’s go back to your path to becoming a writer. How were you able to make this a profession? I wasn’t a sort of weird little writing kid. I was a weird little painting kid. I thought I would be some kind of visual artist until about halfway through college, I began to see a few other students who were more talented, less talented—who knows—but were just fixated on the idea of trying to do justice to a model or a bowl of fruit in paint. I wasn’t quite like that, and I saw that there was a difference. I started writing terrible little stories, just because I liked stories, and I took a class. For slightly mysterious reasons, I knew pretty early on that I had this sort of bottomless interest in the fundamental problem of summoning something like life using only ink, paper, and words in the dictionary. I’ve come to feel that there’s a slightly fine line between having some kind of talent, which you do have to have, but also this fixation. You have to be somebody who will sit in the chair and sit in the chair and sit in the chair and write the sentence 20 times until it begins to take on life. Over the years, I’ve known a certain number of really gifted writers who don’t have that thing. Marilyn Monroe said, “I wasn’t the prettiest, I wasn’t the most talented, I just wanted it more than anybody else.”

Comments