Paul Elie on Literature, Faith, and the Culture of Encounter

- Jun 30, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 4, 2025

A PREVIEW OF HIS WIT LITERARY FESTIVAL CONVERSATION THIS SEPTEMBER

By Scott Edward Anderson

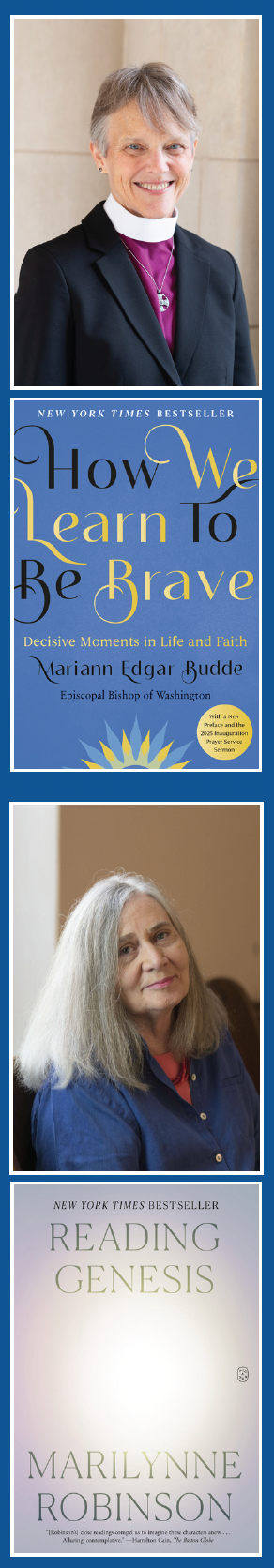

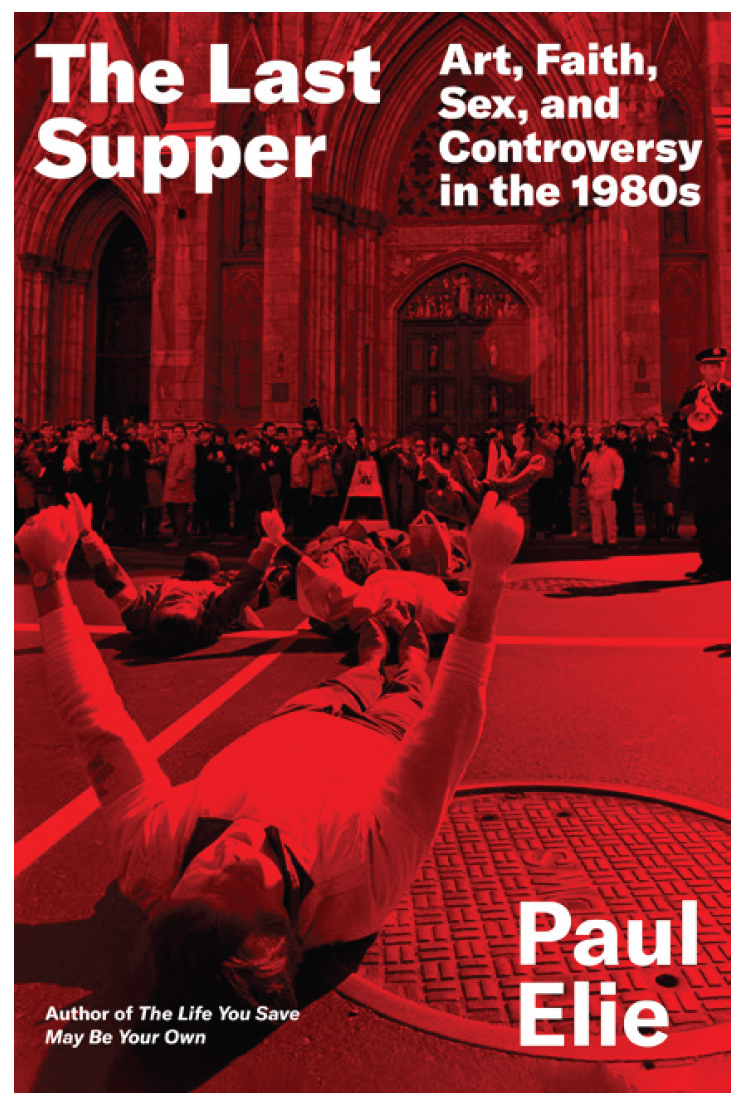

AS THE ANNUAL Author’s Guild WIT (Words, Ideas, and Thinkers) Literary Festival approaches, anticipation builds for a thought-provoking dialogue featuring three distinguished voices: Marilynne Robinson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of over a dozen books of fiction and nonfiction; Bishop Mariann Budde, the Episcopal bishop of Washington, D.C., perhaps best known for her bold sermon at the National Cathedral in January 2025; and Paul Elie, the renowned writer whose new book, The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex, and Controversy in the 1980s, explores the “crypto-religious” art of that turbulent decade. (The term was coined by Polish writer Czeslaw Milosz and describes a way of engaging with religion that is both critical and creative.) WIT festival attendees can expect a serious and generous conversation about belief, imagination, and responsibility in our age. We spoke with Elie, who will lead the WIT festival conversation. Consider this a preview of the rich exchange to come.

In our divided society, what role can spirituality play in fostering connection? It can invite us to consider the very premise that we are a divided society. Yes, there’s a political divide in the U.S., but our divisions are minor compared to those in Israel and Palestine, the Baltic region, or the Sudan. Sound religion, cognizant of history and recognizing the human community is one, can help us recognize that our present sense of social division is what Freud called “the narcissism of minor difference,” and ours is still a relatively stable, prosperous, and peaceful society.

How do you maintain dialogue with those who hold different beliefs? Through what Pope Francis called the “culture of encounter.” You recognize that all of us are equals—kings, princes, bishops, scholars, laborers. And you recognize that you aren’t entirely clear about your own beliefs; they are continually open to adaptation or revision. The encounter with the other is an opportunity to understand one’s own beliefs better, through what the Catholic Worker Movement calls “further clarification of thought.”

How does literature offer a space for spiritual exploration that traditional religion might not? Literature gives us access to the inner and imaginative lives of characters and authors alike. It’s a deep form of the “culture of encounter.” We can see “as if” from the point of view of Mrs. Dalloway, Francis “Ironweed” Phelan, or Rev. Ames—and, where there is religious dimension, we can encounter belief “as if” from Charles Ryder in Brideshead Revisited, the poet Lucille Clifton, or the memoir-artist Christian Wiman.

What gives you hope in today’s cultural landscape? Our public culture is no longer prone to posit the simple idea that religion is in decline, full stop. The paradox of the post-secular era—extending roughly from 1979 to the present, with 9/11 at its center—is that religion in the U.S. seems to be declining and surging at once. What gives me hope is the broader recognition that religion is a fact on the ground and is not going anywhere—as seen in the attention given to Pope Francis’s death and the election of Pope Leo.

How might we reclaim nuanced public conversation about faith? In the way I am trying to model here: Evaluate the premises (our divided society is less so than commonly thought), recognize the complexity of the situation (religion is declining and surging at once), foster a “culture of encounter,” and look to literature and the arts—not just to politics— as a fund of character, insight, imagery, narrative, and wisdom.

How does your writing process relate to your spiritual practice? My spiritual practice is shaped, informally, by the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, in particular the act called the “composition of place.” When I write, I serve to “compose the place” in a double sense: I strive to make myself present in the moment I am committing to the act of writing and to make present imaginatively the place being evoked in the writing—whether it is the old Logos Bookshop in New York or the Anglo-American world of the 1980s where The Last Supper “takes place.”

Your new book, The Last Supper, examines art, faith, and controversy in the 1980s. How does that era’s spiritual wrestling compare with our current moment? This moment and that one have plenty in common: a worldly president boosted by the religious right, grinding wars declared and undeclared, a media eager to consecrate the age as “The Reagan Eighties” or “The Age of Trump.” What’s different is that in that moment, there was a permeable boundary between belief and unbelief and disbelief— as seen in the “crypto-religious” work my book explores. The introduction of violence into that discourse through Ayatollah Khomeini’s call for the death of Salman Rushdie—prompting terrible violence against Rushdie only two years ago—changed the calculus and hardened the lines between belief and unbelief. Terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in 1993 and 2001 played a role in this hardening, too.

What’s the relationship between doubt and faith in your work? My work deals with people of faith—mid-century American Catholic writers, J.S. Bach and his modern, electronically empowered interpreters, the “crypto-religious” artists depicted in The Last Supper. Giving sustained attention to their lives and work has left me in awe of just how deep their faith goes. I’ve been sustained and deepened through the encounter.

How do you write about transcendent experiences in ways that feel authentic? I think of myself as a narrative artist, and, in three books, I’ve had the opportunity to extend a long and complex narrative arc three times. Each book took years to write, so to extend those arcs of narrative time across the chronological time of my own life, and my family’s life, has been transcendent in a very real way. To transcend means “to climb over”—a notion I explore in Reinventing Bach as “technical transcendence.” I feel lucky, even graced, to have entered and extended narrative on three occasions in three decades.

What do you hope will come out of your dialogue with Marilynne Robinson and Bishop Budde this September, and what should attendees of the WIT Literary Festival look forward to? What I hope attendees experience is not just insight, but an invitation— into a wider, deeper conversation about belief, imagination, and responsibility in our time.

The Authors Guild Foundation returns to the Berkshires for its fourth annual WIT Literary Festival, September 25–28, with a theme in 2025 of The Power of Words: Authors & Activism.

In addition to the program with Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde, Marilynne Robinson, and Paul Elie, the festival will feature a lineup that includes M. Gessen, Torrey Peters, Chase Strangio, J. Wortham, Valeria Luiselli, Sanaz Toossi, Dr. Peter Hotez, Catherine Coleman Flowers, Tim Weiner, Imani Perry, Hanif Abdurraqib, Michael S. Roth, and Anna Deavere Smith.

Please visit the Authors Guild Foundation’s website for more information on how to support the festival and purchase tickets:

Even though there are a lot of complicated, expensive video games out there, basic browser-based games still win over players everywhere. One of these games is Snow Rider 3D, a fast-paced sledding game with smooth 3D visuals, simple controls, and the ability to play it over and over again. At first glance, Snow Rider 3D may seem easy, but it offers a fun and rewarding experience that keeps players going back for more. The game is fun since it is easy to play, hard to beat, and has a holiday feel to it.